|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

Great Lakes Shipping

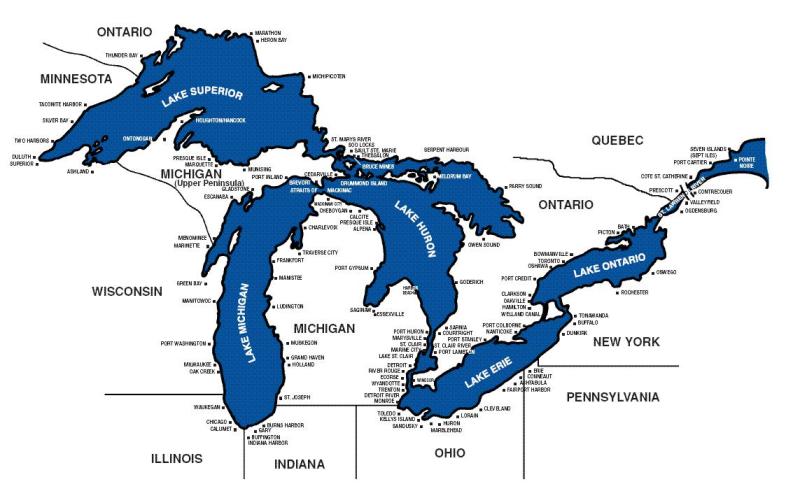

The Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway System is a deep draft waterway extending 3,700 km (2,340 miles) from the Atlantic Ocean to the head of the Great Lakes, in the heart of North America. The St. Lawrence Seaway portion of the System extends from Montreal to mid-Lake Erie. Ranked as one of the outstanding engineering feats of the twentieth century, the St. Lawrence Seaway includes 13 Canadian and 2 U.S. locks. The Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway system is a modern expressway, allowing smooth, seamless movement of waterborne cargo on a 2,340-mile deepwater route extending from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the western end of Lake Superior. More than 300 million metric tons of cargo move along the waterway annually, including domestic and U.S.-Canadian trade within the Lakes and international import-export trade via the Seaway. Twenty-four major ports in Canada and the United States, plus a number of smaller ports, harbors and private dock facilities provide services in the market. On the U.S. side alone, more than 152,000 jobs are related to cargo movement on the system. Bulk cargoes such as iron ore, coal, grain, cement, stone, potash, limestone, sand and salt are primary commodities which move within the region both domestically and internationally. The system also handles project cargoes, containers, forest products, petroleum products, chemicals, edible oils, nonferrous metals and other materials.The Seaway provides access to major North American markets, directly serving the provinces of Ontario and Quebec and the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The St. Lawrence river was discovered by the explorer Thomas Aubert in 1508. The French explorer Jacques Cartier ascended the St. Lawrence river as far as the Indian village of Hochelaga (now Montreal) in 1534. Lake Huron was the first of the Great Lakes to be discovered. In 1615 the French explorers Le Caron and Champlain both discovered Lake Huron but in separate parties. Both explorers came up the St. Lawrence as far as Montreal and then up the Ottawa river. They then took different routes across the country to Georgian Bay and into Lake Huron. The exploring parties met in the Lake Huron region and joined forces. Lake Ontario was discovered the same year on the return trip. Lake Erie was the last of the lakes to be discovered. Joliet discovered Lake Erie in 1669. Lake Superior was discovered in 1629 by the French explorer Brule. Lake Michigan was discovered in 1634 by the French explorer Nicolet. The first recorded passage of the Detroit river by white man was in 1670 by two French priests. The first white man to see the Niagara Falls is supposed to have been the explorer Brule. The French explorer La Salle built the first vessel on the Great Lakes in 1679. The first American vessel to be built on the Great Lakes was the "Washington," built at Erie (then Presque Isle) in 1797. In 1812 a vessel called the "Fur Trader" was built on Lake Superior and after being used in the fur business for awhile she was run over the rapids at the Soo in the attempt to get her to the lower lakes. But she was almost completely wrecked in the attempt. Another little vessel, the Mink, was run over the rapids in 1817 and sustained but little damage. A 96 ton brig was built for service on Lake Erie in 1814, but was soon laid up as being too big to successfully do business on the lakes. The first steamer built on the Great Lakes was the "Ontario" built at Sacketts harbor in 1816. She was a vessel of 232 tons. The Canadian steamer "Frontenac" was built during the same year. But the first steamer built on Lake Erie, for up-lake service, was the "Walk-in-the-Water," built at Buffalo in 1818. The steamer is described on another page. In 1826 the first steamer sailed on Lake Michigan. Regular passenger service was established to Chicago in 1830. In 1836 the first shipment came into Buffalo when the brig "John Kenzie" brought in 3,000 bushels of wheat. The first steamers from Buffalo ventured only as far as Detroit. The first locomotive used in Chicago was carried there in a sail vessel in 1837. The first grain elevator was built in Buffalo in 1842. The first steamer to use propellers instead of paddle wheels was the "Vandalia" built at Oswego in 1841. The first steamer on Lake Michigan was the "Independence" in 1845. The Independence came from Chicago and was portaged around the Soo rapids. The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River have been major North American trade arteries since long before the U.S. or Canada achieved nationhood. Today, this integrated navigation system serves miners, farmers, factory workers and commercial interests from the western prairies to the eastern seaboard.

Virtually every commodity imaginable moves on the Great Lakes Seaway System. system. Annual commerce on the System exceeds 200 million net tons (180 million metric tons), and there is still ample room for growth. Some commodities are dominant:

The primary carrier vessels fall into three main groups: the resident Great Lakes bulk carriers or "lakers"; ocean ships or "salties"; and tug-propelled barges. U.S. and Canadian lakers move cargo among Great Lakes ports, with both nations' laws reserving domestic commerce to their own flag carriers. Salties flying the flags of other nations connect the Lakes with all parts of the world. To realize the magnitude of this commerce, consider the impact of some typical cargoes:

For every ton of cargo, there are scores - often hundreds - of human faces behind the scenes. On board, there are the mariners themselves, while shore side there are lock operators and longshoremen, vessel agents and freight forwarders, ship chandlers and shipyard workers, stevedores and terminal operators, Coast Guard personnel and port officials, railroad workers and truck drivers - a wide web of service providers. Opened to navigation in 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway part of the system has moved more than 2.5 billion metric tons of cargo in 50 years, with an estimated value of more than $375 billion. Almost 25 percent of this cargo travels to and from overseas ports, especially Europe, South America, the Middle East, and Africa. From Great Lakes / Seaway ports, a multi-modal transportation network fans out across the continent. More than 40 provincial and interstate highways and nearly 30 rail lines link the 15 major ports of the system and 50 regional ports with consumers, products and industries all over North America.

Lock Systems

The Seaway Canals The Seaway system is connected by 6 short canals with a total length of less than 60 nautical miles. There are 19 locks, filled and emptied by gravity.

The Seaway Locks Together, the locks make up the world's most spectacular lift system. Ships measuring up to 225.5 metres in length (or 740 feet) and 23.8 metres (or 78 feet), in the beam are routinely raised to more than 180 metres above sea level, as high as a 60-story building. The ships are twice as long and half as wide as a football field and carry cargoes the equivalent of 25,000 metric tonnes. Lock lore: Each lock is 233.5 metres long (766 feet), 24.4 metres wide (80 feet) and 9.1 metres deep (30 feet) over the sill. A lock fills with approximately 91 million litres of water (24 million gallons) in just 7 to 10 minutes. Getting through a lock takes about 45 minutes.

|