|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

Tornadoes

Tornadoes occur in many parts of the world, including Australia, Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America. Even New Zealand reports about 20 tornadoes each year. Two of the highest concentrations of tornadoes outside the U.S. are Argentina and Bangladesh. Both have similar topography with mountains helping catch low-level moisture from over Brazil (Argentina) or from the Indian Ocean (Bangladesh). About 1,000 tornadoes hit the U.S. yearly. Since official tornado records only date back to 1950, we do not know the actual average number of tornadoes that occur each year. Plus, tornado spotting and reporting methods have changed a lot over the last several decades. A tornado is defined as a violently rotating column of air extending from a thunderstorm to the ground. The most violent tornadoes are capable of tremendous destruction with wind speeds of 250 mph or more. Damage paths can be in excess of one mile wide and 50 miles long. Tornado season usually refers to the time of year where the U.S. sees the most tornadoes. The peak “tornado season” for the southern plains -- often referred to as Tornado Alley -- is during May into early June. On the Gulf coast, it is earlier during the spring. In the northern plains and upper Midwest, tornado season is in June or July. But, remember, tornadoes can happen at any time of year. Tornadoes can also happen at any time of day, but most tornadoes occur between 4-9 p.m.

Thunderstorms develop in warm, moist air in advance of eastward-moving cold fronts. These thunderstorms often produce large hail, strong winds, and tornadoes. Tornadoes in the winter and early spring are often associated with strong, frontal systems that form in the Central States and move east. Occasionally, large outbreaks of tornadoes occur with this type of weather pattern. Several states may be affected by numerous severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. During the spring in the Central Plains, thunderstorms frequently develop along a "dryline," which separates very warm, moist air to the east from hot, dry air to the west. Tornado-producing thunderstorms mayform as the dryline moves east during the afternoon hours. Along the front range of the Rocky Mountains, in the Texas panhandle, and in the southern High Plains, thunderstorms frequently form as air near the ground flows "upslope" toward higher terrain. If other favorableconditions exist, these thunderstorms can produce tornadoes. Tornadoes occasionally accompany tropical storms and hurricanes that move over land. Tornadoes are most common to the right and ahead of the path of the storm center as it comes onshore. Tornado Alley is a nickname for an area that consistently experiences a high frequency of tornadoes each year. The area that has the most strong and violent tornadoes includes eastern SD, NE, KS, OK. Northern TX, and eastern Colorado. The relatively flat land in the Great Plains allows cold dry polar air from Canada to meet warm moist tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico. A large number of tornadoes form when these two air masses meet, along a phenomenon known as a "dryline."

The dryline is a boundary separating hot, dry air to the west from warm, moist air to the east. You can see it on a weather map by looking for sharp changes in dew point temperatures. Between adjacent weather stations the differences in dew point can vary by as much as 40 degrees or more. The dryline is usually found along the western high plains. Air moving down the eastern slopes of the Rockies warms and dries as it sinks onto the plains, creating a hot, dry, cloud-free zone. During the day, it moves eastward mixing up the warm moist air ahead of it. If there is enough moisture and instability in the warm air, severe storms can form - because the dryline is the "push" the air needs to start moving up! During the evening, the dryline "retreats" and drifts back to the west. The next day the cycle can start all over again, until a larger weather system pushes through and washes it away.

Tornado Myths:MYTH:

Areas near rivers, lakes, and mountains are safe from tornadoes. MYTH: The

low pressure with a tornado causes buildings to "explode" as the tornado

passes overhead.

MYTH:

Windows should be opened before a tornado approaches to equalize pressure

and minimize damage. What does a tornadic storm look like?Forecasters and storm spotters have learned to recognize certain thunderstorm features and structure that make tornado formation more likely. Some of these are visual cues, like the rear-flank downdraft, and others are particular patterns in radar images, like the tornadic vortex signature (TVS). VISUAL EVIDENCE The most reliable evidence of a tornado is for someone who has been trained to recognize tornadoes to actually see one. Storm spotters report what they see to the National Weather Service and provide important information to warning forecasters who must make critical warning decisions. Storm spotters can be emergency managers or even local people with a keen interest in severe weather who have undergone formal storm spotter training in their community. Some of the features storm spotters and forecasters look for in tornadic storms include:

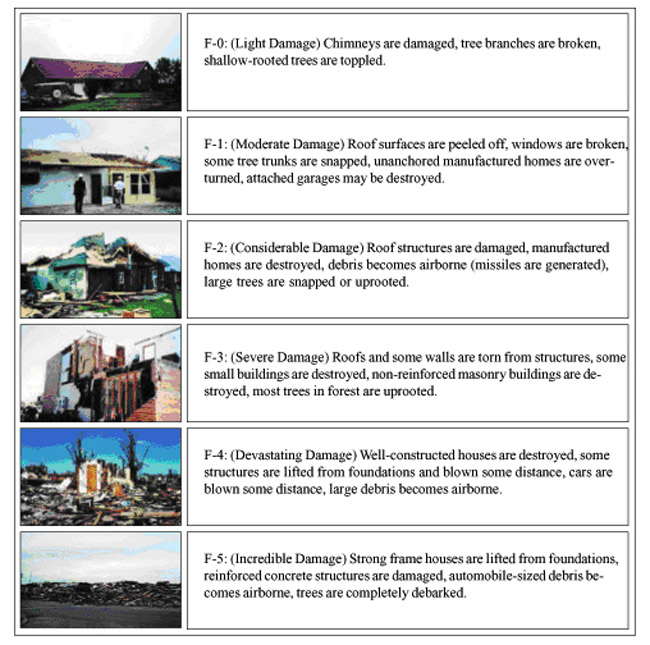

The Fujita Tornado Scale, usually referred to as the F-Scale, classifies tornadoes based on the resulting damage. This scale was developed by Dr. T. Theodore Fujita (University of Chicago) in 1971.

*** IMPORTANT NOTE ABOUT ENHANCED F-SCALE WINDS: The Enhanced F-scale still is a set of wind estimates (not measurements) based on damage. Its uses three-second gusts estimated at the point of damage based on a judgment of 8 levels of damage to the 28 indicators listed below. These estimates vary with height and exposure. Important: The 3 second gust is not the same wind as in standard surface observations. Standard measurements are taken by weather stations in open exposures, using a directly measured, "one minute mile" speed. If you hear a "Tornado Warning" seek safety immediately. Indoors:

In a vehicle:

Outdoors:

NOAA, National Geographic, ABC, The Weather Channel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||