|

NASA Finds Thickest Parts of Arctic Ice Cap Melting Faster

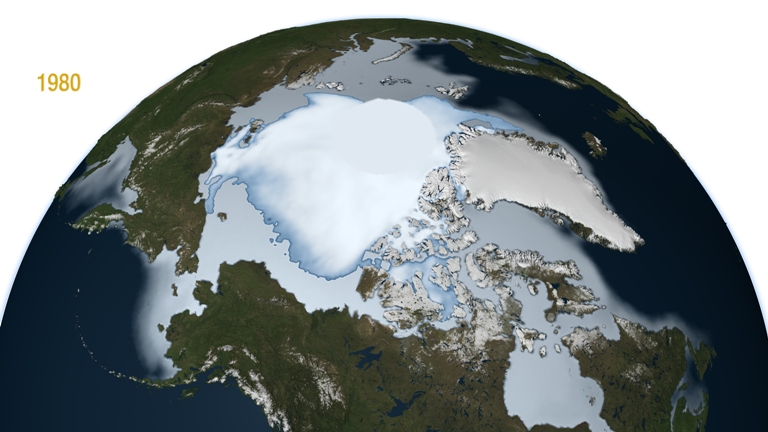

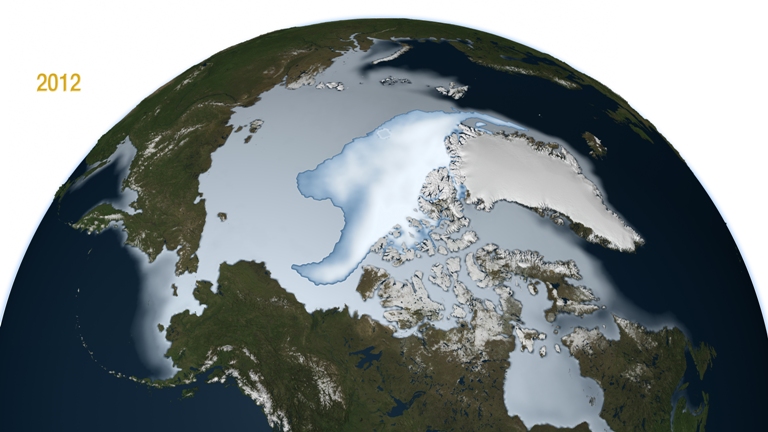

These iages illustrates how

perennial sea ice has declined from 1980 to 2012. The bright white central mass

shows the perennial sea ice while the larger light blue area shows the full

extent of the winter sea ice including the average annual sea ice during the

months of November, December and January. The data shown here were compiled by

NASA senior research scientist Josefino Comiso from NASA's Nimbus-7 satellite

and the U.S. Department of Defense's Defense Meteorological Satellite Program.

Credit: NASA/Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio.

NASA Goddard

GREENBELT, Md. -- A new NASA study revealed that the oldest and thickest Arctic

sea ice is disappearing at a faster rate than the younger and thinner ice at the

edges of the Arctic Ocean’s floating ice cap.

The thicker ice, known as multi-year ice, survives through the cyclical summer

melt season, when young ice that has formed over winter just as quickly melts

again. The rapid disappearance of older ice makes Arctic sea ice even more

vulnerable to further decline in the summer, said Joey Comiso, senior scientist

at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., and author of the study,

which was recently published in Journal of Climate.

The new research takes a closer look at how multi-year ice, ice that has made it

through at least two summers, has diminished with each passing winter over the

last three decades. Multi-year ice "extent" – which includes all areas of the

Arctic Ocean where multi-year ice covers at least 15 percent of the ocean

surface – is diminishing at a rate of -15.1 percent per decade, the study found.

There’s another measurement that allows researchers to analyze how the ice cap

evolves: multi-year ice "area," which discards areas of open water among ice

floes and focuses exclusively on the regions of the Arctic Ocean that are

completely covered by multi-year ice. Sea ice area is always smaller than sea

ice extent, and it gives scientists the information needed to estimate the total

volume of ice in the Arctic Ocean. Comiso found that multi-year ice area is

shrinking even faster than multi-year ice extent, by -17.2 percent per decade.

"The average thickness of the Arctic sea ice cover is declining because it is

rapidly losing its thick component, the multi-year ice. At the same time, the

surface temperature in the Arctic is going up, which results in a shorter

ice-forming season," Comiso said. "It would take a persistent cold spell for

most multi-year sea ice and other ice types to grow thick enough in the winter

to survive the summer melt season and reverse the trend."

Scientists differentiate multi-year ice from both seasonal ice, which comes and

goes each year, and "perennial" ice, defined as all ice that has survived at

least one summer. In other words: all multi-year ice is perennial ice, but not

all perennial ice is multi-year ice (it can also be second-year ice).

Comiso found that perennial ice extent is shrinking at a rate of -12.2 percent

per decade, while its area is declining at a rate of -13.5 percent per decade.

These numbers indicate that the thickest ice, multiyear-ice, is declining faster

than the other perennial ice that surrounds it.

As perennial ice retreated in the last three decades, it opened up new areas of

the Arctic Ocean that could then be covered by seasonal ice in the winter. A

larger volume of younger ice meant that a larger portion of it made it through

the summer and was available to form second-year ice. This is likely the reason

why the perennial ice cover, which includes second year ice, is not declining as

rapidly as the multiyear ice cover, Comiso said.

Multi-year sea ice hit its record minimum extent in the winter of 2008. That is

when it was reduced to about 55 percent of its average extent since the late

1970s, when satellite measurements of the ice cap began. Multi-year sea ice then

recovered slightly in the three following years, ultimately reaching an extent

34 percent larger than in 2008, but it dipped again in winter of 2012, to its

second lowest extent ever.

For this study, Comiso created a time series of multi-year ice using 32 years of

passive microwave data from NASA's Nimbus-7 satellite and the U.S. Department of

Defense's Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, taken during the winter

months from 1978 to 2011. This is the most robust and longest satellite dataset

of Arctic sea ice extent data to date, Comiso said.

Younger ice, made from recently frozen ocean waters, is saltier than multi-year

ice, which has had more time to drain its salts. The salt content in first- and

second-year ice gives them different electrical properties than multi-year ice:

In winter, when the surface of the sea ice is cold and dry, the microwave

emissivity of multiyear ice is distinctly different from that of first- and

second-year ice. Microwave radiometers on satellites pick up these differences

in emissivity, which are observed as variations in brightness temperature for

the different types of ice. The “brightness” data are used in an algorithm to

discriminate multiyear ice from other types of ice.

Comiso compared the evolution of the extent and area of multi-year ice over

time, and confirmed that its decline has accelerated during the last decade, in

part because of the dramatic decreases of 2008 and 2012. He also detected a

periodic nine-year cycle, where sea ice extent would first grow for a few years,

and then shrink until the cycle started again. This cycle is reminiscent of one

occurring on the opposite pole, known as the Antarctic Circumpolar Wave, which

has been related to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation atmospheric pattern. If the

nine-year Arctic cycle were to be confirmed, it might explain the slight

recovery of the sea ice cover in the three years after it hit its historical

minimum in 2008, Comiso said.

Goddard Release: 12-23

Rani Gran / Maria-José Viñas

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

301-286-2483 / 301-614-5883

rani.c.gran@nasa.gov /

mj.vinas@nasa.gov

|